Voedingsonderzoek blijft verbazen. Moesten we eerst verzadigd vet vervangen door een hoeveelheid linolzuur die onze voorouders nooit hadden kunnen eten, moeten we nu weer melk gaan drinken of calcium slikken om het risico op dikke darmkanker te verlagen (1,2). In dit artikel wordt de achtergrond van het colonkanker risico door (bewerkt) rood vlees onderzocht en wordt de vraag gesteld of we melk en calcium eigenlijk wel nodig hebben om dit risico te verkleinen.

Dikkedarmkanker (colonkanker) is wereldwijd de derde meest voorkomende kanker in mannen en de tweede in vrouwen. Meer dan de helft van de gevallen wordt geconstateerd in de rijke landen, alwaar men relatief veel rood vlees (rund, varken, lam) eet (3). Er is ontegenzeggelijk een sterke relatie met het eten van rood vlees en bewerkt vlees (3-7). Bewerkt vlees is geconserveerd door rijpen, roken, zouten, pekelen of de toevoeging van chemische conserveringsmiddelen, waaronder nitraat en nitriet.

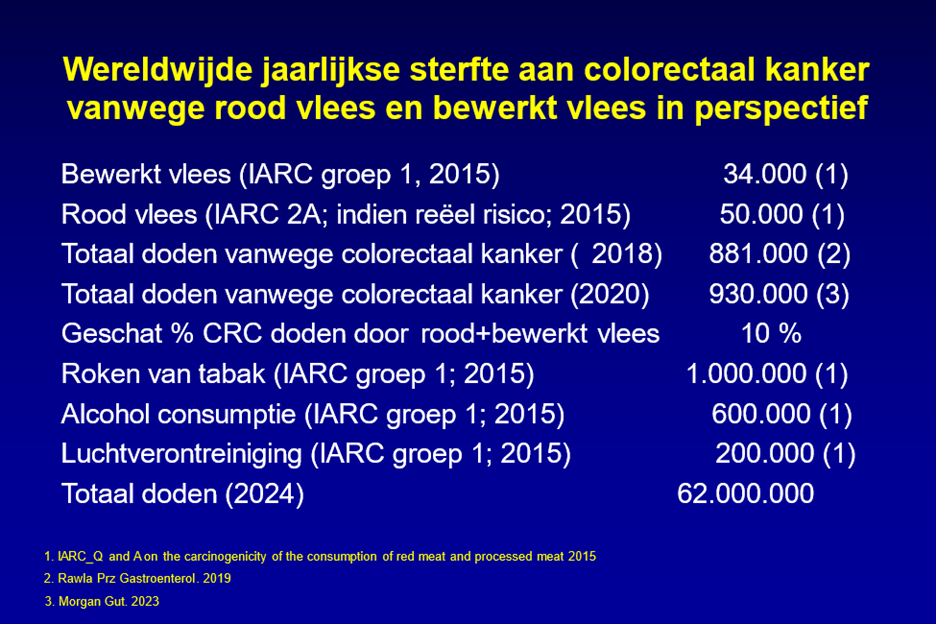

In 2015 plaatste de International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) bewerkt vlees in groep-1 carcinogenen (‘kankerverwekkend in mensen’) en rood vlees in groep-2A (‘mogelijk kankerverwekkend in mensen’). Geschat werd dat wereldwijd jaarlijks 34.000 mensen aan dikkedarmkanker stierven vanwege het eten van bewerkt vlees en 50.000 vanwege rood vlees indien dit inderdaad kankerverwekkend zou zijn (7b). In tabel 1 wordt dit risico in perspectief gezet met het totaal aantal wereldwijde overlijdens aan dikkedarmkanker en andere overlijdensoorzaken die te maken hebben met onze leefstijl. Het gaat volgens de IARC-schattingen dus om een relatief klein percentage aan overlijdens aan dikkedarmkanker, waarbij het grootste deel (rood vlees) onzeker is. Andere oorzaken van dikkedarmkanker zijn: roken, ongezonde voeding, hoge alcoholconsumptie, fysieke inactiviteit en overgewicht (7c,7d).

Een Duitse modelstudie uit 2023 liet zien dat de totale eliminatie van bewerkt vlees het aantal personen met colonkanker met 9,6 procent kan verlagen en dat het volledig weglaten van rood vlees 2,9 procent van colonkanker kan voorkomen. Deze dalingen zijn relatief klein, maar geenszins verwaarloosbaar. Eén van de conclusies was dat er waarschijnlijk aanzienlijk meer gevallen van colorectaal kanker kunnen worden voorkomen door deelname aan screening, het vergroten van de fysieke activiteit, stoppen met roken en de consumptie van alcohol, en het vermijden van overgewicht en obesitas (7f,7g).

Voorkomen melk en calcium dikke darmkanker?

Dat melk, calcium en vitamine D ons vrijwaren van deze belangrijke doodsoorzaak zingt al tientallen jaren rond (8-19). Het werd onlangs maar weer eens bevestigd (20). Hiervoor werden 542.778 vrouwen van gemiddeld 60 jaar gedurende gemiddeld 16,6 jaar gevolgd. Van deze vrouwen kregen in die periode 12.251 (2,3 procent) colonkanker. Deze ziekte werd gelinkt aan hun voedingsgewoonte, waarbij alcohol (per 20 gram per dag; ongeveer gelijk aan 2 flesjes bier, 2 wijntjes) een ongeveer 15 procent hoger risico opleverde. Calcium (per 300 mg per dag; overeenkomend met ongeveer 1 glas melk per dag) scoorde een 17 procent lager risico. Voorts vonden de auteurs (20) hogere colonkankerrisico’s voor de inname van rood vlees en bewerkt vlees en lagere risico’s voor de consumptie van ontbijtgranen, fruit, volle granen, koolhydraten, vezels, totale suikers, foliumzuur en vitamine C. Mensen die vanwege hun genetica meer lactose (uniek voorkomend in melk) kunnen verdragen hadden ook een lager risico op colorectale kanker (20). Op tamelijk overtuigende wijze werd hier, en ook in eerdere studies (8-19), via epidemiologisch onderzoek, aangetoond dat melk en calcium het risico op colonkanker kunnen verlagen.

Rood- en bewerkt vlees geassocieerd met dikke darmkanker

Reeds lang is, eveneens uit epidemiologische studies, bekend dat het eten van rood vlees en bewerkt vlees een sterke relatie vertoont met colonkanker (3-7a,7e), maar bijvoorbeeld ook met diabetes mellitus type 2 (21). Uiteraard werden de experts in Nederland geconsulteerd (1-2). Die telden 1 en 1 bij elkaar op en prompt werd ons geadviseerd dat je maar beter je biertje en wijntje kan laten staan om het te vervangen door een glas melk.

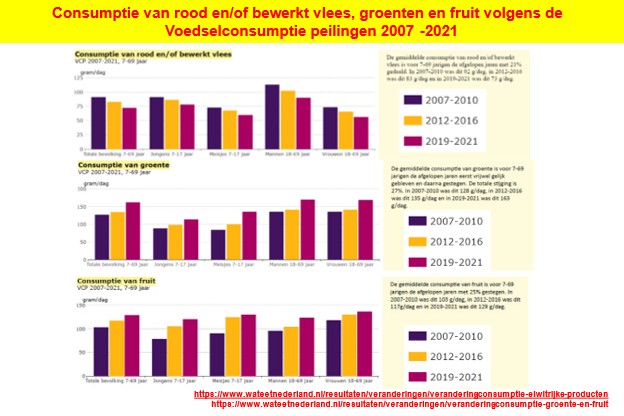

Niemand die zich blijkbaar afvroeg hoe het kan. Want onze voorvaders vóór de landbouwrevolutie deden zich ruim tegoed aan rood vlees. Geschat wordt dat het geslacht Homo in het midden van de paleolithische tijd (2,5 miljoen jaar geleden tot zo’n 11.000 jaar geleden) een voeding had die bestond uit 60 procent dierlijk materiaal en 40 procent plantaardig materiaal. Dat werd gevolgd door een tamelijk abrupte toename van het plantaardige deel naar zo’n 70 procent in de neolithische tijd (11.000 tot 5.000 jaar geleden) (22). Onze hersenen hebben vanaf ongeveer 2 miljoen jaar geleden niet kunnen groeien zonder de consumptie van energie-compacte voedingsbronnen, vooral vlees en vis (22-30). Er is bijvoorbeeld geen enkele herbivoor met een hoog ‘encefalisatie quotiënt’. Dat is het hersengewicht ten opzichte van het totale lichaamsgewicht. Afgezien van de zoogperiode dronk tot 10.000 jaar geleden niemand melk, en zeker niet van een koe. Onze naaste verwanten in het dierenrijk doen dat ook al niet. Critici lanceren daarop meestal de evergreen dat mensen vroeger niet zo oud werden. Dat klopt, maar dat kwam destijds vooral vanwege infectieziektes, honger en geweld (25,26). Deze hebben we tegenwoordig tamelijk goed onder controle en vormen de voornaamste reden dat we tegenwoordig ouder worden dan toen. Bovendien stijgt colonkanker in de laatste tientallen jaren sterk in vele landen bij zowel jongeren (25-49 jaar) als ouderen (50-74 jaar), en ook in Nederland (8a-c). Er is dus iets anders aan de hand, daar kan je niet omheen.

Het melk- of calciumadvies kan, evenals het vervangen van verzadigd vet door meervoudig onverzadigd vet, niet anders worden opgevat als een preventieve maatregel die ten doel heeft om een verhoogd colon kankerrisico te verkleinen dat we zelf hebben veroorzaakt. Het is zinniger om je af te vragen waarom rood vlees tegenwoordig gelinkt is aan colonkanker en vervolgens iets aan de oorzaak te doen. En dus niet weer direct klaar te staan met een preventieve maatregel, die potentieel nieuwe problemen kan veroorzaken (zie verderop).

Mechanismen: wat doen we verkeerd met dat vlees?

De vraag is ‘wat doen we tegenwoordig anders met dat rood vlees. Is het wel hetzelfde materiaal als wat onze voorvaders aten’? Of kan het zijn dat het niet aan het vlees zelf ligt of de bewerking daarvan, maar aan een veranderd voedingspatroon, zoals het eten van teveel vlees ten opzichte van groente/fruit? Er zijn talrijke suggesties inzake de mechanismen die het huidige verhoogde risico op colonkanker zouden kunnen verklaren. In deze bijdrage beperken we ons tot de voeding en het gaat hier dus niet over de grotere colonkanker risico’s van roken, hoge alcoholconsumptie, fysieke inactiviteit en overgewicht. Dat is een duidelijke beperking, want voeding vertoont interactie met elk van deze factoren, terwijl deze factoren onderling eveneens interacteren.

Figuur 1

De belangrijkste voedings-gerelateerde ‘boosdoeners bij colonkanker’ (3) zijn:

- N-nitrosoverbindingen (NOCs; N-nitrosamines en N-nitrosamides)

- Heterocyclische amines (HCAs)

- Polycyclische aromatische koolwaterstoffen (PAHs)

- De ‘ijzer-bevattende haemgroep’ in rood vlees

- Meervoudig onverzadigde vetzuren (PUFAs)

- Galzuren

- Niet menselijk siaalzuur

- Infectieuze agentia

De laatste twee worden niet besproken. De mechanismen kunnen grofweg in twee groepen worden verdeeld: 1) de bereidingswijze van het huidige vlees en 2) de interactie van het huidige vlees met andere nutriënten, zoals onder andere aanwezig in groente en fruit (figuur 1).

Dat de ijzer (Fe2+) bevattende haemgroep in de myoglobine en hemoglobine van rood vlees (optie 4) de directe oorzaak vormt, is vanuit onze evolutionaire achtergrond ongeloofwaardig. Dat ijzer heeft immers altijd al in deze eiwitten gezeten. Voor een directe onafhankelijke invloed van haem-ijzer bestaat dan ook niet veel steun (42a). Het probleem ontstaat eerder door het bakken, braden en grillen van rood vlees (31-40a). Daarbij gaat het onder andere om de aanwezige meervoudig-onverzadigde vetzuren in vlees, maar ook de toegevoegde hoog-geraffineerde meervoudig-onverzadigde oliën (zoals zonnebloemolie) bij de bereiding, zoals het bakken in een pan. Die zijn superkwetsbaar bij verhitting en moesten we zo nodig gaan gebruiken omdat ze ‘ons cholesterol verlagen’. Iedere eerstejaars chemicus kan u vertellen dat het verhitten van (haem) ijzer (Fe2+) met onverzadigde vetzuren een perfecte storm vormt voor het ontstaan van vetzuur (per)oxidatie (41,42,42a,42b). Dat proces kan men ruiken bij het bakken van vlees, waarbij de intensiteit van de daarbij vrij komende aroma’s overeenkomt met de intensiteit van het lipiden peroxidatie proces (31).

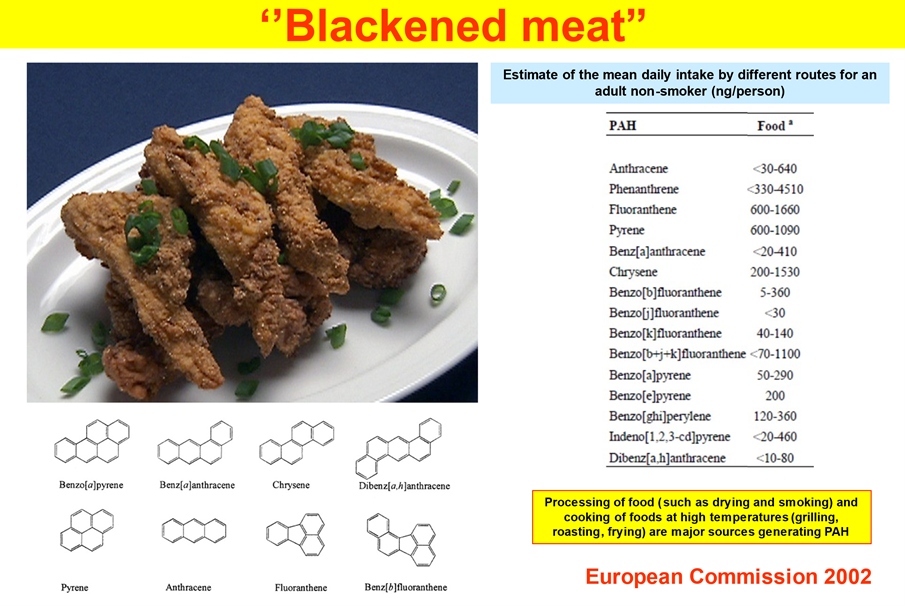

In dit proces ontstaan carcinogene polycyclische aromatische koolwaterstoffen (PAH’s) (optie 3) vanwege de onvolledige verbranding van organisch materiaal, zoals bij het roken, grillen, roosteren en drogen. Vetten en oliën zijn belangrijke bronnen van PAH’s. Benzo(a)pyrene is één van de bekendste (34). Ze ontstaan vooral in vlees dat bereid wordt tot wat tegenwoordig heet ‘well-done’ en nog erger: ‘blackened (figuur 2). In modelsystemen worden ze bij verhitten gemakkelijker gemaakt uit meervoudig-onverzadigde vetzuren, dan uit mono-onverzadigde- en verzadigde- vetzuren. Hun productie neemt toe met het aantal dubbele bindingen in het vetzuur, en naarmate de temperatuur hoger wordt neemt ook de vorming van de meer potente carcinogene PAH’s toe (36,42). Door het ‘vetmesten’ van slachtvee is het vetgehalte van hun vlees toegenomen en daarmee de kans op het ontstaan van PAH’s bij de bereiding (48,49).

Figuur 2

Andere schadelijke ‘bewerkings-contaminanten’ die bij verhitting kunnen worden gemaakt zijn de (pro)kanker-verwekkende heterocyclische aromatische amines (HAA’s) (optie 2), N-nitrosoverbindingen (NA’s) (optie 1) en acrylamide. De HCA- en N-nitrosamine gehaltes stijgen, evenals de PAH’s, met de temperatuur en de expositie duur in de volgorde: (diep)frituren, grillen, oven roosteren, koken. Het HCA-gehalte stijgt proportioneel met het verzadigd vet gehalte in het vlees en de hoeveelheid vet stijgt met het ‘vetmesten’ van het slachtvee. N-nitrosamines worden gemaakt door verhitting van vlees waaraan nitraat en nitriet zijn toegevoegd voor het conserveren, maar ze ontstaan ook in onbewerkt vlees. Acrylamide is een product van de ‘Maillard reactie’, waarin een primair amine (in de aminozuren van eiwitten) met een suiker reageert naar een ‘Schiffse base’, die vervolgens uiteenvalt in o.a. acrylamide (32).

Het gaat hier dus om een combinatie van de opties 1 tot en met 5, en niet om rood vlees of ijzer per sé. IJzer treedt bij vele, zo niet elk, van deze processen op als katalysator en dat komt overeen met het verschil in colonkanker risico tussen rood en wit vlees. De werkelijke oorzaak zou dan zijn het gebruik van te hoge temperaturen, gebruik van nitraat/nitriet voor conserveren, hoog vetgehalte in vlees en de bereiding in hoog geraffineerde meervoudig-onverzadigde vetzuren die nagenoeg geen bescherming genieten tegen (per)oxidatie. Het gebruik van verzadigde vetten in bijvoorbeeld boter of kokosnootolie veroorzaakt in ieder geval minder (per)oxidatie. Als kruiden (fytochemicaliën) bij het bakken worden toegevoegd wordt dit peroxidatieproces sterk afgeremd (32,37,43,47,48,49).

Ironisch is dat het toevoegen van kruiden neerkomt op het toevoegen in de pan van fytochemicaliën, die het huidige slachtvee wordt onthouden in hun voer. Want in vlees van wilde dieren zitten die kruiden van nature en die dieren hebben ook een lager vetgehalte. Deze ‘fytochemicaliën’ in ‘wild vlees’ veroorzaken de typische ‘wildsmaak’. Het vlees dat we tegenwoordig eten bevat deze ‘kruiden’ niet (48,49). Ook wordt het gebruik van meervoudig onverzadigde vetzuren meestal vertaald naar een hoge inname van linolzuur (een omega-6 vetzuur, bijvoorbeeld in zonnebloemolie), wat de omega-3 status door competitie verlaagt. Hierdoor wordt een gestarte ontstekingsreactie minder goed gestopt (50,51). De hieruit voortkomende toestand van ‘laaggradige ontsteking’ kan uitmonden in kanker (52-59).

Enkele van de bovengenoemde processen gebeuren ook los van de bereiding van het vlees in ons lichaam. Via de ‘N-nitrosoweg’ (figuur 1) ontstaan eveneens carcinogene nitrosamines (NA’s) en wel uit zowel bewerkt- als vers- vlees. Via de peroxidatie weg ontstaan reactieve stoffen zoals DHN-MA, TBARS, MDA en 4-HNE die schade kunnen veroorzaken. Calcium en fytochemicaliën, chlorofyl en antioxidantia zoals vitamines C en E uit planten voorkomen deze reacties of beschermen tegen hun gevolgen (42a). Calcium kan ook galzuren (optie 6) en vrije vetzuren in onze darmen binden. In hun vrije vorm kunnen galzuren en vrije vetzuren onze darmwand irriteren waardoor kanker kan ontstaan(3,7a,60). Het gaat daarbij vooral om de galzuren die door de bacteriën in de dikke darm worden gemaakt (de zogenaamde secundaire galzuren) uit de galzuren die we zelf in de lever maken (de primaire galzuren). Maar dat gebeurde in het verleden altijd al, en strookt weer niet met wat onze voorvaders deden en de recente sterke stijging van colonkanker. Wat kan dan de reden zijn dat die galzuren en vrije vetzuren dat tegenwoordig wel doen?

Vrije vetzuren ontstaan door splitsing van voedingsvet in onze dunne darm en galzuren hebben we nodig om ze aldaar op te nemen. Een hoge vetinname via de typisch Westerse voeding verhoogt de afscheiding van galzuren in de darmen, met meer kans op lokale ontstekingen, gevolgd door verlies van cellen en een hogere deling van de epitheelcellen van de darm om dit verlies te compenseren (3,7a,60). Een verhoogde celdelingsactiviteit verhoogt op haar beurt de kans op kanker vanwege foutjes in het DNA die tijdens de celdeling worden gemaakt. Naar schatting ontstaat twee-derde deel van alle tumoren bij de mens door niet-gerepareerde foutjes die spontaan tijdens de celdeling worden gemaakt (61,62).

In het besproken artikel (20) werd niet geopperd dat het kan gaan om een tekort aan vitamine C. Vitamine C halen we nagenoeg volledig uit groente en fruit. Dat past naadloos bij de observatie van de auteurs dat naast vitamine C ook fruit en vezels geassocieerd waren met minder colonkanker. Als je veel rood vlees eet, dan eet je immers minder van iets anders, hier dus waarschijnlijk groente en fruit. Colonkanker wordt ook reeds lang geassocieerd met het eten van onvoldoende groente en fruit (63-66,7e). Hoe zou dat kunnen werken? We komen dan weer op optie 1: de N-nitrosoverbindingen (NOCs). Deze verbindingen zijn aangetoond in de ontlasting van vrijwilligers na het eten van rood vlees. Ze ontstaan, behalve bij het verhitten, ook uit een spontane reactie van (onder andere) twee nitrietmoleculen met elkaar in een zure omgeving, dus vooral in de maag. Nitriet wordt toegevoegd aan vlees om de groei van micro-organismen en daarmee infecties te voorkomen. Het wordt ook gemaakt uit nitraat (dat we voor zo’n 80 procent krijgen uit groente) door bacteriën in de mondholte. De reactie van nitriet waarbij nitrosamines ontstaan in de maag, gebeurt echter niet in de aanwezigheid van vitamine C, want onder invloed van vitamine C reageert het nitriet naar stikstof-monooxide (NO). NO heeft gunstige eigenschappen, zoals het doden van lokale micro-organismen (waaronder helicobacter pylori) en de verlaging van de bloeddruk (49,49,67-76). Nitrosamines zijn daarentegen carcinogeen: ze kunnen ons DNA ‘alkyleren’. Bestudering van het DNA uit colontumoren toonde inderdaad mutaties die worden beschouwd als de ‘sporen van alkylering’. Deze sporen hadden een relatie met een hoge inname van zowel bewerkt als onbewerkt rood vlees, en naarmate deze sporen intenser waren was de overleving slechter (77). De vraag is dus of rood en bewerkt vlees de schuld hebben, dan wel een tekort aan vitamine C en andere antioxidantia zoals de fytochemicaliën in planten. Dat doet dus eerder denken aan teveel vlees ten opzichte van groente en fruit en het reeds genoemde verhitten van rood vlees tot een te hoge temperatuur. Eigenlijk zou er geen nitriet meer mogen worden toegevoegd aan vlees zonder dat er niet ook vitamine C aan wordt toegevoegd (75a).

De nadelen van melk en calcium

‘Ieder voordeel heb zijn nadeel’, en dat is hier ook het geval. Zuivelgebruik is in westerse landen weliswaar gerelateerd aan minder colonkanker (8-20), maar ook aan meer prostaatkanker (79). Een studie uit 2022 met een half miljoen Chinezen associeerde zuivel aan totaal-, lever- en borstkanker en mogelijk lymfomen (80).

Het is nagenoeg onmogelijk om de huidige aanbeveling van 950-1.200 mg calcium per dag te halen zonder melk(producten) te gebruiken. Je vraagt je af hoe onze voorouders dat hebben overleefd en hoe ze dat in ontwikkelingslanden, met meestal minder osteoporose, doen. De botten van onze voorouders vertonen geen osteoporotische fracturen (116-119). De huidige richtlijn voor patiënten met osteoporose adviseert om een calciumsupplement te gebruiken van 500-1.000 mg per dag, indien de inname van calcium lager is dan 1.000-1.200 mg per dag (80). Dit advies doet de totaal calciuminname al snel stijgen tot boven de 1.400 mg per dag. De osteoporose-calcium connectie baseert zich vooral op een studie met kwetsbare ouderen die een te lage calciuminname hadden (81). Dergelijke positieve resultaten zijn nooit gevonden in studies met op zichzelf wonende personen in de gemeenschap (82). De voordelen van calciumsupplementen voor osteoporose zijn dus dubieus, maar er zijn wel nadelen.

Calcium en magnesium zijn antagonisten, wat betekent dat een hoge inname van calcium uit melk of supplementen de neiging heeft om onze magnesiumstatus aan te tasten. Het kan leiden tot een verstoorde calcium/magnesium balans (83-88). In een 19 jaar prospectieve studie van 61.433 Zweedse vrouwen was een totale calciuminname van ³1400 mg/dag, ten opzichte van van 600-1.000 mg per dag, geassocieerd met een hoger sterfterisico aan alle oorzaken, hart en vaatziekte en ischemische hartziekte, maar niet met beroerte (89). Een meta-analyse van calcium monotherapie gaf aan dat 5 jaar calciumsuppletie van 1.000 ouderen 14 meer myocardinfarcten, 10 meer beroertes, en 13 meer doden oplevert, tegenover 26 minder fracturen (90-96). De potentieel schadelijke effecten van calcium blijven doorgaans onvermeld als we weer eens uit de pers vernemen dat melk en calcium het ontstaan van colonkanker in de gezonde bevolking kunnen voorkomen.

De moraal van dit verhaal

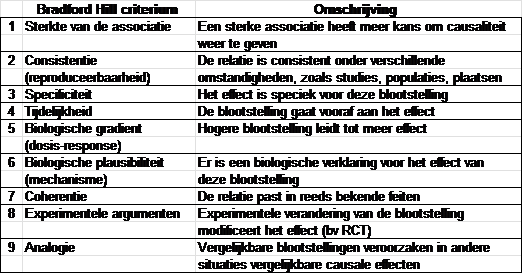

Rood vlees bevat vele belangrijke (micro)nutriënten, waaronder ijzer (114). Voedingsonderzoek is veel moeilijker dan het onderzoek van geneesmiddelen. Voedingsonderzoek ten behoeve van de volksgezondheid is bedoeld voor de preventie van ziekte in gezonde personen; geneesmiddelen zijn bedoeld voor patiënten. Vele ziektes, inclusief colonkanker, ontstaan op zeer lange termijn en de typisch westerse ziektes worden voor naar schatting meer dan 85 procent veroorzaakt door onze leefstijl (97,97a). Voedingsonderzoek kan zich niet meten met het placebo-gecontroleerd dubbelblind onderzoek dat vereist is voor het registeren van geneesmiddelen. De oplossing is om te kijken naar het ‘totaal aan bewijs’, zoals vervat in de ‘Bradford-Hill criteria voor causaliteit’ (tabel 2, 98). Het is vanuit een evolutionair en biologisch oogpunt (criterium 6) ongeloofwaardig dat rood vlees op zichzelf ongezond voor ons zou zijn. Zolang het mechanisme van de associatie van rood vlees met colonkanker onduidelijk is, is een pragmatische oplossing door melk of calcium aan te raden prematuur en potentieel gecontra-indiceerd.

Tabel 2

Het lijkt belangrijk om geen adviezen te geven die niet stroken met onze fysiologie (‘ons normale functioneren’). Deze fysiologie heeft een evolutionaire achtergrond en wordt bestudeerd in de discipline van de ‘evolutionaire geneeskunde’ (99-113). Zoals gesteld door Omaye en Omaye: ‘Waarschijnlijk kun je je vlees hebben en het ook nog eens eten, zolang je er ook voldoende fruit en groenten bij consumeert’ (115). Een advies om voor de preventie van colonkanker melk te gaan drinken of calciumsupplementen te gebruiken brengt ons nog verder van een gezonde interactie van de mens met de natuur. Deze interactie heeft ons in miljoenen jaren gemaakt tot wie we nog steeds zijn. Willen we doorgaan met onze huidige ongezonde leefstijl dan is het calciumadvies ter voorkoming van colonkanker misschien nog niet zo slecht. Maar dan moeten we de keerzijde (meer hart en vaatziekte) vanwege deze ‘therapie’ eveneens omarmen. De voorkeur gaat naar het aanpakken van de oorzaak en niet een van de vele gevolgen.

Deze tekst is in eenvoudige taal hier te lezen.

Referenties

ombosis

Colon cancer and milk/calcium in the media

1. “Elke dag een glas melk helpt tegen kanker”. Hoogleraar zet feiten en fabels over voeding en kanker op een rij. 11 februari 2025, accessed 19 februari 2025

2. Hoe je de kans op kanker vermindert met voeding: ‘Eén glas melk per dag helpt al’. Ma 17 februari 17:30, Villa VdB, accessed 19 februari 2025

Colon cancer and red/processed meat

3. Aykan NF. Red Meat and Colorectal Cancer. Oncol Rev. 2015 Dec 28;9(1):288. doi: 10.4081/oncol.2015.288. PMID: 26779313; PMCID: PMC4698595.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26779313

4. Knuppel A, Papier K, Fensom GK, Appleby PN, Schmidt JA, Tong TYN, Travis RC, Key TJ, Perez-Cornago A. Meat intake and cancer risk: prospective analyses in UK Biobank. Int J Epidemiol. 2020 Oct 1;49(5):1540-1552. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa142. PMID: 32814947.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32814947

5. Bradbury KE, Murphy N, Key TJ. Diet and colorectal cancer in UK Biobank: a prospective study. Int J Epidemiol. 2020 Feb 1;49(1):246-258. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz064. PMID: 30993317; PMCID: PMC7124508.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30993317

6. Norat T, Bingham S, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Jenab M, Mazuir M, Overvad K, Olsen A, Tjønneland A, Clavel F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Kesse E, Boeing H, Bergmann MM, Nieters A, Linseisen J, Trichopoulou A, Trichopoulos D, Tountas Y, Berrino F, Palli D, Panico S, Tumino R, Vineis P, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Peeters PH, Engeset D, Lund E, Skeie G, Ardanaz E, González C, Navarro C, Quirós JR, Sanchez MJ, Berglund G, Mattisson I, Hallmans G, Palmqvist R, Day NE, Khaw KT, Key TJ, San Joaquin M, Hémon B, Saracci R, Kaaks R, Riboli E. Meat, fish, and colorectal cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into cancer and nutrition. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005 Jun 15;97(12):906-16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji164. PMID: 15956652; PMCID: PMC1913932.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15956652

7. De Filippo C, Chioccioli S, Meriggi N, Troise AD, Vitali F, Mejia Monroy M, Özsezen S, Tortora K, Balvay A, Maudet C, Naud N, Fouché E, Buisson C, Dupuy J, Bézirard V, Chevolleau S, Tondereau V, Theodorou V, Maslo C, Aubry P, Etienne C, Giovannelli L, Longo V, Scaloni A, Cavalieri D, Bouwman J, Pierre F, Gérard P, Guéraud F, Caderni G. Gut microbiota drives colon cancer risk associated with diet: a comparative analysis of meat-based and pesco-vegetarian diets. Microbiome. 2024 Sep 27;12(1):180. doi: 10.1186/s40168-024-01900-2. PMID: 39334498; PMCID: PMC11438057.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39334498

7a. Bruce WR. Recent hypotheses for the origin of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1987 Aug 15;47(16):4237-42. PMID: 3300962.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3300962

7b. WHO. Cancer: Carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat 26 October 2015 | Questions and answers, accessed 27/2/2025

7c. Rawla P, Sunkara T, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14(2):89-103. doi: 10.5114/pg.2018.81072. Epub 2019 Jan 6. PMID: 31616522; PMCID: PMC6791134.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31616522

7d. Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N, Bray F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023 Feb;72(2):338-344. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327736. Epub 2022 Sep 8. PMID: 36604116.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36604116

7e. Figueiredo JC, Hsu L, Hutter CM, Lin Y, Campbell PT, Baron JA, Berndt SI, Jiao S, Casey G, Fortini B, Chan AT, Cotterchio M, Lemire M, Gallinger S, Harrison TA, Le Marchand L, Newcomb PA, Slattery ML, Caan BJ, Carlson CS, Zanke BW, Rosse SA, Brenner H, Giovannucci EL, Wu K, Chang-Claude J, Chanock SJ, Curtis KR, Duggan D, Gong J, Haile RW, Hayes RB, Hoffmeister M, Hopper JL, Jenkins MA, Kolonel LN, Qu C, Rudolph A, Schoen RE, Schumacher FR, Seminara D, Stelling DL, Thibodeau SN, Thornquist M, Warnick GS, Henderson BE, Ulrich CM, Gauderman WJ, Potter JD, White E, Peters U; CCFR; GECCO. Genome-wide diet-gene interaction analyses for risk of colorectal cancer. PLoS Genet. 2014 Apr 17;10(4):e1004228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004228. PMID: 24743840; PMCID: PMC3990510.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24743840

7f. Niedermaier T, Gredner T, Hoffmeister M, Mons U, Brenner H. Impact of Reducing Intake of Red and Processed Meat on Colorectal Cancer Incidence in Germany 2020 to 2050-A Simulation Study. Nutrients. 2023 Feb 17;15(4):1020. doi: 10.3390/nu15041020. PMID: 36839378; PMCID: PMC9966277.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36839378

7g. World Cancer Research Fund. Eating less processed meat reduces bowel cancer risk, accessed 28-02-2025

https://www.wcrf.org/about-us/news-and-blogs/eating-less-processed-meat-reduces-bowel-cancer-risk

Colon cancer, milk, calcium and vitamin D

8. Barrubés L, Babio N, Becerra-Tomás N, Rosique-Esteban N, Salas-Salvadó J. Association Between Dairy Product Consumption and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiologic Studies. Adv Nutr. 2019 May 1;10(suppl_2):S190-S211. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy114. Erratum in: Adv Nutr. 2020 Jul 1;11(4):1055-1057. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa071. PMID: 31089733; PMCID: PMC6518136.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31089733

8a. Sung H, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Jiang C, Morgan E, Zahwe M, Cao Y, Bray F, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer incidence trends in younger versus older adults: an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet Oncol. 2025 Jan;26(1):51-63. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00600-4. Epub 2024 Dec 12. PMID: 39674189; PMCID: PMC11695264.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39674189

8b. Tang X, Peng J, Huang S, Xu H, Wang P, Jiang J, Zhang W, Shi X, Shi L, Zhong X, Lü M. Global burden of early-onset colorectal cancer among people aged 40-49 years from 1990 to 2019 and predictions to 2030. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023 Dec;149(18):16537-16550. doi: 10.1007/s00432-023-05395-6. Epub 2023 Sep 15. PMID: 37712957.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37712957

8c. Yang X, Wu D, Liu Y, He Z, Manyande A, Fu H, Xiang H. Global disease burden linked to diet high in red meat and colorectal cancer from 1990 to 2019 and its prediction up to 2030. Front Nutr. 2024 Mar 14;11:1366553. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1366553. PMID: 38549751; PMCID: PMC10973012.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38549751

9. Jin S, Kim Y, Je Y. Dairy Consumption and Risks of Colorectal Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Meta-analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020 Nov;29(11):2309-2322. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0127. Epub 2020 Aug 27. PMID: 32855265.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32855265

10. Han S, Yao J, Yamazaki H, Streicher SA, Rao J, Nianogo RA, Zhang Z, Huang BZ. Genetically Determined Circulating Lactase/Phlorizin Hydrolase Concentrations and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Nutrients. 2024 Mar 12;16(6):808. doi: 10.3390/nu16060808. PMID: 38542719; PMCID: PMC10975724.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38542719

11. Lopez-Caleya JF, Ortega-Valín L, Fernández-Villa T, Delgado-Rodríguez M, Martín-Sánchez V, Molina AJ. The role of calcium and vitamin D dietary intake on risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2022 Feb;33(2):167-182. doi: 10.1007/s10552-021-01512-3. Epub 2021 Oct 27. PMID: 34708323.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34708323

12. Zouiouich S, Wahl D, Liao LM, Hong HG, Sinha R, Loftfield E. Calcium Intake and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2025 Feb 3;8(2):e2460283. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.60283. PMID: 39960668; PMCID: PMC11833519.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39960668

13. Park Y, Leitzmann MF, Subar AF, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A. Dairy food, calcium, and risk of cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Feb 23;169(4):391-401. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.578. PMID: 19237724; PMCID: PMC2796799.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19237724

14. Han C, Shin A, Lee J, Lee J, Park JW, Oh JH, Kim J. Dietary calcium intake and the risk of colorectal cancer: a case control study. BMC Cancer. 2015 Dec 16;15:966. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1963-9. PMID: 26675033; PMCID: PMC4682267.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26675033

15. Zhang X, Fang YJ, Feng XL, Abulimiti A, Huang CY, Luo H, Zhang NQ, Chen YM, Zhang CX. Higher intakes of dietary vitamin D, calcium and dairy products are inversely associated with the risk of colorectal cancer: a case-control study in China. Br J Nutr. 2020 Mar 28;123(6):699-711. doi: 10.1017/S000711451900326X. Epub 2019 Dec 12. PMID: 31826765.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31826765

16. Carroll C, Cooper K, Papaioannou D, Hind D, Pilgrim H, Tappenden P. Supplemental calcium in the chemoprevention of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2010 May;32(5):789-803. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.04.024. PMID: 20685491.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20685491

17. Weingarten MA, Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J. Dietary calcium supplementation for preventing colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;2008(1):CD003548. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003548.pub4. PMID: 18254022; PMCID: PMC8719254.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18254022

18. Lofano K, Principi M, Scavo MP, Pricci M, Ierardi E, Di Leo A. Dietary lifestyle and colorectal cancer onset, recurrence, and survival: myth or reality? J Gastrointest Cancer. 2013 Mar;44(1):1-11. doi: 10.1007/s12029-012-9425-y. PMID: 22878898.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22878898

19. Heine-Bröring RC, Winkels RM, Renkema JM, Kragt L, van Orten-Luiten AC, Tigchelaar EF, Chan DS, Norat T, Kampman E. Dietary supplement use and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cancer. 2015 May 15;136(10):2388-401. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29277. Epub 2014 Nov 11. PMID: 25335850.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25335850

20. Papier K, Bradbury KE, Balkwill A, Barnes I, Smith-Byrne K, Gunter MJ, Berndt SI, Le Marchand L, Wu AH, Peters U, Beral V, Key TJ, Reeves GK. Diet-wide analyses for risk of colorectal cancer: prospective study of 12,251 incident cases among 542,778 women in the UK. Nat Commun. 2025 Jan 8;16(1):375. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-55219-5. PMID: 39779669; PMCID: PMC11711514.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39779669

Diabetes mellitus type 2 and red meat

21. Li C, Bishop TRP, Imamura F, Sharp SJ, Pearce M, Brage S, Ong KK, Ahsan H, Bes-Rastrollo M, Beulens JWJ, den Braver N, Byberg L, Canhada S, Chen Z, Chung HF, Cortés-Valencia A, Djousse L, Drouin-Chartier JP, Du H, Du S, Duncan BB, Gaziano JM, Gordon-Larsen P, Goto A, Haghighatdoost F, Härkänen T, Hashemian M, Hu FB, Ittermann T, Järvinen R, Kakkoura MG, Neelakantan N, Knekt P, Lajous M, Li Y, Magliano DJ, Malekzadeh R, Le Marchand L, Marques-Vidal P, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Maskarinec G, Mishra GD, Mohammadifard N, O’Donoghue G, O’Gorman D, Popkin B, Poustchi H, Sarrafzadegan N, Sawada N, Schmidt MI, Shaw JE, Soedamah-Muthu S, Stern D, Tong L, van Dam RM, Völzke H, Willett WC, Wolk A, Yu C; EPIC-InterAct Consortium; Forouhi NG, Wareham NJ. Meat consumption and incident type 2 diabetes: an individual-participant federated meta-analysis of 1·97 million adults with 100 000 incident cases from 31 cohorts in 20 countries. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024 Sep;12(9):619-630. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00179-7. Erratum in: Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025 Feb;13(2):e2. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(25)00002-6. PMID: 39174161.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39174161

Ancestral meat intake and disease

22. Ben-Dor M, Sirtoli R, Barkai R. The evolution of the human trophic level during the Pleistocene. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2021 Aug;175 Suppl 72:27-56. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.24247. Epub 2021 Mar 5. PMID: 33675083

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33675083

23. Muskiet, F. A. J. (2005). Evolutionaire geneeskunde U bent wat u eet, maar u moet weer worden wat u at. Ned Tijdschr Klin Chem Labgeneesk, 30(3), 163-184.

24. Milton K. The critical role played by animal source foods in human (Homo) evolution. J Nutr. 2003 Nov;133(11 Suppl 2):3886S-3892S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3886S. PMID: 14672286.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14672286

25. Eaton SB, Cordain L, Lindeberg S. Evolutionary health promotion: a consideration of common counterarguments. Prev Med. 2002 Feb;34(2):119-23. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0966. PMID: 11817904.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11817904

26. Hill K, Hurtado AM, Walker RS. High adult mortality among Hiwi hunter-gatherers: implications for human evolution. J Hum Evol. 2007 Apr;52(4):443-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.11.003. Epub 2006 Dec 8. PMID: 17289113.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17289113

27. Mann NJ. A brief history of meat in the human diet and current health implications. Meat Sci. 2018 Oct;144:169-179. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.06.008. Epub 2018 Jun 13. PMID: 29945745.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29945745

28. Richards MP. A brief review of the archaeological evidence for Palaeolithic and Neolithic subsistence. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002 Dec;56(12):16 p following 1262. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601646. PMID: 12494313.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12494313

29. Aiello, L. C., & Wheeler, P. (1995). The expensive-tissue hypothesis: the brain and the digestive system in human and primate evolution. Current anthropology, 36(2), 199-221.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/204350

30. Cordain L, Watkins BA, Mann NJ. Fatty acid composition and energy density of foods available to African hominids. Evolutionary implications for human brain development. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2001;90:144-61. doi: 10.1159/000059813. PMID: 11545040.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11545040

Iron, PAHs, HCAs, N-nitrosamines, PUFAs, heating

31. Li Z, Frank D, Ha M, Hastie M, Warner RD. Hemoglobin and free iron influence the aroma of cooked beef by influencing the formation and release of volatiles. Food Chem. 2024 Mar 30;437(Pt 1):137794. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137794. Epub 2023 Oct 19. PMID: 37926028.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37926028

32. Iammarino M, Marino R, Nardelli V, Ingegno M, Albenzio M. Red Meat Heating Processes, Toxic Compounds Production and Nutritional Parameters Changes: What about Risk-Benefit? Foods. 2024 Jan 30;13(3):445. doi: 10.3390/foods13030445. PMID: 38338580; PMCID: PMC10855356.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38338580

33. Szabo Z, Marosvölgyi T, Szabo E, Koczka V, Verzar Z, Figler M, Decsi T. Effects of Repeated Heating on Fatty Acid Composition of Plant-Based Cooking Oils. Foods. 2022 Jan 12;11(2):192. doi: 10.3390/foods11020192. PMID: 35053923; PMCID: PMC8774349.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8774349

34. Bukowska B, Mokra K, Michałowicz J. Benzo[a]pyrene-Environmental Occurrence, Human Exposure, and Mechanisms of Toxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jun 6;23(11):6348. doi: 10.3390/ijms23116348. PMID: 35683027; PMCID: PMC9181839.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9181839

35. Bruce WR. Recent hypotheses for the origin of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1987 Aug 15;47(16):4237-42. PMID: 3300962.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3300962

36. Nie W, Cai K, Li Y, Tu Z, Hu B, Zhou C, Chen C, Jiang S. Study of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons generated from fatty acids by a model system. J Sci Food Agric. 2019 May;99(7):3548-3554. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.9575. Epub 2019 Mar 6. PMID: 30623971.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30623971

37. Nadeem HR, Akhtar S, Ismail T, Sestili P, Lorenzo JM, Ranjha MMAN, Jooste L, Hano C, Aadil RM. Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines in Meat: Formation, Isolation, Risk Assessment, and Inhibitory Effect of Plant Extracts. Foods. 2021 Jun 24;10(7):1466. doi: 10.3390/foods10071466. PMID: 34202792; PMCID: PMC8307633.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34202792

38. Sampaio GR, Guizellini GM, da Silva SA, de Almeida AP, Pinaffi-Langley ACC, Rogero MM, de Camargo AC, Torres EAFS. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Foods: Biological Effects, Legislation, Occurrence, Analytical Methods, and Strategies to Reduce Their Formation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jun 2;22(11):6010. doi: 10.3390/ijms22116010. PMID: 34199457; PMCID: PMC8199595.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34199457

39. Directorate, C., & Opinions, S. (2002). Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on the risks to human health of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in food.

https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-12/sci-com_scf_out153_en.pdf

40. Oncology Nurse Advisor. Chemicals in Meat Cooked at High Temperatures and Cancer Risk (Fact Sheet). Publish DateJuly 9, 2019

40a. Yousefi, M. H., Masoudi, A., Rounkian, M. S., Mansouri, M., Hojat, B., Samani, M. K., … & Saeb11, S. (2025). An overview of the current evidences on the role of iron in colorectal cancer: a review.

41. Frankel 2nd, E. N. (2005). Lipid oxidation 2nd edition. Dundee, Scotland: The Oily Press LTD.

https://shop.elsevier.com/books/lipid-oxidation/frankel/978-0-9531949-8-8

42. Morales A, Marmesat S, Dobarganes MC, Márquez-Ruiz G, Velasco J. Quantitative analysis of hydroperoxy-, keto- and hydroxy-dienes in refined vegetable oils. J Chromatogr A. 2012 Mar 16;1229:190-7. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.01.039. Epub 2012 Jan 24. PMID: 22321954.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22321954

42a. Corpet DE. Red meat and colon cancer: should we become vegetarians, or can we make meat safer? Meat Sci. 2011 Nov;89(3):310-6. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.04.009. Epub 2011 Apr 17. PMID: 21558046.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21558046

42b. Bastide NM, Pierre FH, Corpet DE. Heme iron from meat and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis and a review of the mechanisms involved. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011 Feb;4(2):177-84. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0113. Epub 2011 Jan 5. PMID: 21209396.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21209396

43. Bulanda S, Janoszka B. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Roasted Pork Meat and the Effect of Dried Fruits on PAH Content. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar 10;20(6):4922. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20064922. PMID: 36981831; PMCID: PMC10049194.

44. Sivasubramanian BP, Dave M, Panchal V, Saifa-Bonsu J, Konka S, Noei F, Nagaraj S, Terpari U, Savani P, Vekaria PH, Samala Venkata V, Manjani L. Comprehensive Review of Red Meat Consumption and the Risk of Cancer. Cureus. 2023 Sep 15;15(9):e45324. doi: 10.7759/cureus.45324. PMID: 37849565; PMCID: PMC10577092.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37849565

45. Qigang N, Afra A, Ramírez-Coronel AA, Turki Jalil A, Mohammadi MJ, Gatea MA, Efriza, Asban P, Mousavi SK, Kanani P, Mombeni Kazemi F, Hormati M, Kiani F. The effect of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon biomarkers on cardiovascular diseases. Rev Environ Health. 2023 Oct 2. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2023-0070. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37775307.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37775307

46. Domínguez R, Pateiro M, Gagaoua M, Barba FJ, Zhang W, Lorenzo JM. A Comprehensive Review on Lipid Oxidation in Meat and Meat Products. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019 Sep 25;8(10):429. doi: 10.3390/antiox8100429. PMID: 31557858; PMCID: PMC6827023.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31557858

47. Beddows CG, Jagait C, Kelly MJ. Preservation of alpha-tocopherol in sunflower oil by herbs and spices. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2000 Sep;51(5):327-39. doi: 10.1080/096374800426920. PMID: 11103298.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11103298

48. Muskiet FAJ, Schaafsma G. Waarom zijn groente en fruit gezond deel 1. Voedingsgeneeskunde 2025;25(6)44-53

49. Muskiet FAJ, Schaafsma G. Waarom zijn groente en fruit gezond deel 2. Voedingsgeneeskunde Voedingsgeneeskunde 2025;26(1)34-44

Fish and low grade inflammation

50. Muskiet FAJ. Hoeveel vis(olie) is voldoende? Uitzicht 2025(2)10-14, in press.

51. Muskiet FAJ. Vis(olie) is nog steeds gezond. Voedingsgeneeskunde 2025, in press.

Chronic inflammation and cancer

52. Multhoff G, Molls M, Radons J. Chronic inflammation in cancer development. Front Immunol. 2012 Jan 12;2:98. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00098. PMID: 22566887; PMCID: PMC3342348.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22566887

53. Greten FR, Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and Cancer: Triggers, Mechanisms, and Consequences. Immunity. 2019 Jul 16;51(1):27-41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025. PMID: 31315034; PMCID: PMC6831096.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31315034

54. Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002 Dec 19-26;420(6917):860-7. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. PMID: 12490959; PMCID: PMC2803035.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12490959

55. Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001 Feb 17;357(9255):539-45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. PMID: 11229684.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11229684

56. Sfanos KS, De Marzo AM. Prostate cancer and inflammation: the evidence. Histopathology. 2012 Jan;60(1):199-215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04033.x. PMID: 22212087; PMCID: PMC4029103.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22212087

57. Zitvogel L, Pietrocola F, Kroemer G. Nutrition, inflammation and cancer. Nat Immunol. 2017 Jul 19;18(8):843-850. doi: 10.1038/ni.3754. PMID: 28722707.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28722707

58. Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med. 2010 Dec 1;49(11):1603-16. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006. Epub 2010 Sep 16. PMID: 20840865; PMCID: PMC2990475.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20840865

59. Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Sundaram C, Harikumar KB, Tharakan ST, Lai OS, Sung B, Aggarwal BB. Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes. Pharm Res. 2008 Sep;25(9):2097-116. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9661-9. Epub 2008 Jul 15. Erratum in: Pharm Res. 2008 Sep;25(9):2200. Kunnumakara, Ajaikumar B [corrected to Kunnumakkara, Ajaikumar B]. PMID: 18626751; PMCID: PMC2515569.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18626751

Colon cancer and bile acids

60. Bruce WR. Recent hypotheses for the origin of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1987 Aug 15;47(16):4237-42. PMID: 3300962.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3300962

61. Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B. Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science. 2015 Jan 2;347(6217):78-81. doi: 10.1126/science.1260825. PMID: 25554788; PMCID: PMC4446723.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25554788

62. Muskiet FAJ. Kanker als stomme pech, maakt de evolutie er een zooitje van? Uitzicht 2021(9)25.

Colon cancer and vegetables/fruits

63. Pyo Y, Kwon KH, Jung YJ. Anticancer Potential of Flavonoids: Their Role in Cancer Prevention and Health Benefits. Foods. 2024 Jul 17;13(14):2253. doi: 10.3390/foods13142253. PMID: 39063337; PMCID: PMC11276387.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39063337

64. Alahmari LA. Dietary fiber influence on overall health, with an emphasis on CVD, diabetes, obesity, colon cancer, and inflammation. Front Nutr. 2024 Dec 13;11:1510564. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1510564. PMID: 39734671; PMCID: PMC11671356.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39734671

65. Wesselink E, Boshuizen HC, van Lanen AS, Kok DE, Derksen JWG, Smit KC, de Wilt JHW, Koopman M, May AM, Kampman E, van Duijnhoven FJB; COLON and PLCRC studies. Dietary and lifestyle inflammation scores in relation to colorectal cancer recurrence and all-cause mortality: A longitudinal analysis. Clin Nutr. 2024 Sep;43(9):2092-2101. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2024.07.028. Epub 2024 Jul 26. PMID: 39094474.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39094474

66. Kampman E, Verhoeven D, Sloots L, van ’t Veer P. Vegetable and animal products as determinants of colon cancer risk in Dutch men and women. Cancer Causes Control. 1995 May;6(3):225-34. doi: 10.1007/BF00051794. PMID: 7612802.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7612802

Health effects of nitrate and nitrite

67. Bryan NS, Ivy JL. Inorganic nitrite and nitrate: evidence to support consideration as dietary nutrients. Nutr Res. 2015 Aug;35(8):643-54. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2015.06.001. Epub 2015 Jun 11. PMID: 26189149.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26189149

68. Bryan NS. Nitric oxide deficiency is a primary driver of hypertension. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022 Dec;206:115325. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115325. Epub 2022 Nov 5. PMID: 36349641..

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36349641

69. Say Yes to NO -Nitric Oxide as the magic molecule to Erections and Vascular Health |Nathan Bryan PhD, accessed 22 October 2024

70. Nitric Oxide and Functional Health – with Dr. Nathan Bryan | The Empowering Neurologist EP. 166, accessed 22 October 2024

71. Banez MJ, Geluz MI, Chandra A, Hamdan T, Biswas OS, Bryan NS, Von Schwarz ER. A systemic review on the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol, curcumin, and dietary nitric oxide supplementation on human cardiovascular health. Nutr Res. 2020 Jun;78:11-26. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2020.03.002. Epub 2020 Mar 10. PMID: 32428778.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32428778

72. Bryan NS, Burleigh MC, Easton C. The oral microbiome, nitric oxide and exercise performance. Nitric Oxide. 2022 Aug 1;125-126:23-30. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2022.05.004. Epub 2022 May 28. PMID: 35636654.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35636654

73. Bryan NS, Ahmed S, Lefer DJ, Hord N, von Schwarz ER. Dietary nitrate biochemistry and physiology. An update on clinical benefits and mechanisms of action. Nitric Oxide. 2023 Mar 1;132:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2023.01.003. Epub 2023 Jan 20. PMID: 36690137.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36690137

74. Nitric Oxide: The Holy Grail Of Inflammation & Disease – Fix This For Longevity | Dr. Nathan Bryan, accessed 22 Ocober 2024

75. Bryan HK, Olayanju A, Goldring CE, Park BK. The Nrf2 cell defence pathway: Keap1-dependent and -independent mechanisms of regulation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013 Mar 15;85(6):705-17. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.11.016. Epub 2012 Dec 5. PMID: 23219527.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23219527

75a. Hord NG, Tang Y, Bryan NS. Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jul;90(1):1-10. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27131. Epub 2009 May 13. PMID: 19439460.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19439460

76. Oliveira-Paula GH, Pinheiro LC, Tanus-Santos JE. Mechanisms impairing blood pressure responses to nitrite and nitrate. Nitric Oxide. 2019 Apr 1;85:35-43. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2019.01.015. Epub 2019 Feb 1. PMID: 30716418.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30716418

Alkylating Signature in Colorectal Cancer

77. Gurjao C, Zhong R, Haruki K, Li YY, Spurr LF, Lee-Six H, Reardon B, Ugai T, Zhang X, Cherniack AD, Song M, Van Allen EM, Meyerhardt JA, Nowak JA, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS, Wu K, Ogino S, Giannakis M. Discovery and Features of an Alkylating Signature in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2021 Oct;11(10):2446-2455. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1656. Epub 2021 Jun 17. PMID: 34140290; PMCID: PMC8487940.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34140290

Risks of dairy and calcium

78. Aune D, Navarro Rosenblatt DA, Chan DS, Vieira AR, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Vatten LJ, Norat T. Dairy products, calcium, and prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Jan;101(1):87-117. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.067157. Epub 2014 Nov 19. PMID: 25527754.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25527754

79. Kakkoura MG, Du H, Guo Y, Yu C, Yang L, Pei P, Chen Y, Sansome S, Chan WC, Yang X, Fan L, Lv J, Chen J, Li L, Key TJ, Chen Z; China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB) Collaborative Group. Dairy consumption and risks of total and site-specific cancers in Chinese adults: an 11-year prospective study of 0.5 million people. BMC Med. 2022 May 6;20(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02330-3. PMID: 35513801; PMCID: PMC9074208.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35513801

80. Richtlijn Osteoporose en Fractuurpreventie, derde herziening. 2011, ISBN: 978-94-90826-11-6

https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/files/2020-05/osteoporose-en-fractuurpreventie.pdf

81. Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Delmas PD, Meunier PJ. Effect of calcium and cholecalciferol treatment for three years on hip fractures in elderly women. BMJ. 1994 Apr 23;308(6936):1081-2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6936.1081. PMID: 8173430; PMCID: PMC2539939.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8173430

82. Reid IR. Should we prescribe calcium supplements for osteoporosis prevention? J Bone Metab. 2014 Feb;21(1):21-8. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2014.21.1.21. Epub 2014 Feb 28. PMID: 24707464; PMCID: PMC3970298.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24707464

83. Muskiet FAJ. Calcium-magnesiumratio in de voeding belangrijk voor adequate magnesiumstatus deel 1. Voedingsgeneeskunde 2023;24(3)46-54

84. Muskiet FAJ. Calcium-magnesiumratio in de voeding belangrijk voor adequate magnesiumstatus deel 2. Voedingsgeneeskunde 2023;24(4)44-55

85. Fouhy LE, Mangano KM, Zhang X, Hughes BD, Tucker KL, Noel SE. Association between a Calcium-to-Magnesium Ratio and Osteoporosis among Puerto Rican Adults. J Nutr. 2023 Sep;153(9):2642-2650. doi: 10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.05.009. Epub 2023 May 9. PMID: 37164266; PMCID: PMC10550845.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37164266

86. Rosanoff A. Rising Ca:Mg intake ratio from food in USA Adults: a concern? Magnes Res. 2010 Dec;23(4):S181-93. doi: 10.1684/mrh.2010.0221. Epub 2011 Jan 14. PMID: 21233058.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21233058

87. Costello RB, Rosanoff A, Dai Q, Saldanha LG, Potischman NA. Perspective: Characterization of Dietary Supplements Containing Calcium and Magnesium and Their Respective Ratio-Is a Rising Ratio a Cause for Concern? Adv Nutr. 2021 Mar 31;12(2):291-297. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa160. PMID: 33367519; PMCID: PMC8264923.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33367519

88. Rosanoff A, Weaver CM, Rude RK. Suboptimal magnesium status in the United States: are the health consequences underestimated? Nutr Rev. 2012 Mar;70(3):153-64. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00465.x. Epub 2012 Feb 15. PMID: 22364157.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22364157

89. Michaëlsson K, Melhus H, Warensjö Lemming E, Wolk A, Byberg L. Long term calcium intake and rates of all cause and cardiovascular mortality: community based prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2013 Feb 12;346:f228. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f228. PMID: 23403980; PMCID: PMC3571949.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23403980

90. Reid IR, Bolland MJ. Calcium supplements: bad for the heart? Heart. 2012 Jun;98(12):895-6. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301904. PMID: 22626897.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22626897

91. Reid IR, Bristow SM, Bolland MJ. Calcium supplements: benefits and risks. J Intern Med. 2015 Oct;278(4):354-68. doi: 10.1111/joim.12394. Epub 2015 Jul 14. Erratum in: J Intern Med. 2016 Mar;279(3):311. doi: 10.1111/joim.12474. PMID: 26174589.

92. Reid IR, Bolland MJ, Grey A. Does calcium supplementation increase cardiovascular risk? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010 Dec;73(6):689-95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03792.x. PMID: 20184602.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20184602

93. Reid IR. Should we prescribe calcium supplements for osteoporosis prevention? J Bone Metab. 2014 Feb;21(1):21-8. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2014.21.1.21. Epub 2014 Feb 28. PMID: 24707464; PMCID: PMC3970298.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24707464

94. Reid IR. Calcium Supplementation- Efficacy and Safety. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2025 Feb 12;23(1):8. doi: 10.1007/s11914-025-00904-7. PMID: 39937345; PMCID: PMC11821691.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39937345

95. Reid IR, Bristow SM, Bolland MJ. Cardiovascular complications of calcium supplements. J Cell Biochem. 2015 Apr;116(4):494-501. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25028. PMID: 25491763.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25491763

96. Hill, J., Miller, D., & Verma, S. (2023). Does calcium supplementation increase cardiovascular disease risk in postmenopausal women?. Evidence-Based Practice, 26(4), 16-17.

https://journals.lww.com/ebp/citation/2023/04000/does_calcium_supplementation_increase.12.aspx

Lifestyle and disease

97. Willett WC. Balancing life-style and genomics research for disease prevention. Science. 2002 Apr 26;296(5568):695-8. doi: 10.1126/science.1071055. PMID: 11976443.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11976443

87a. de la Chapelle A. Genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004 Oct;4(10):769-80. doi: 10.1038/nrc1453. PMID: 15510158.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15510158

Evidence in nutrition

98. HILL AB. THE ENVIRONMENT AND DISEASE: ASSOCIATION OR CAUSATION? Proc R Soc Med. 1965 May;58(5):295-300. PMID: 14283879; PMCID: PMC1898525.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14283879

Evolutionary Medine

99. Nesse RM, Stearns SC. The great opportunity: Evolutionary applications to medicine and public health. Evol Appl. 2008 Feb;1(1):28-48. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2007.00006.x. PMID: 25567489; PMCID: PMC3352398.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25567489

100. Straub RH. Evolutionary medicine and chronic inflammatory state–known and new concepts in pathophysiology. J Mol Med (Berl). 2012 May;90(5):523-34. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0861-8. Epub 2012 Jan 22. PMID: 22271169; PMCID: PMC3354326.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22271169

101. Gluckman PD, Bergstrom CT. Evolutionary biology within medicine: a perspective of growing value. BMJ. 2011 Dec 19;343:d7671. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7671. PMID: 22184558; PMCID: PMC3281315.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22184558

102. Stearns SC, Nesse RM, Govindaraju DR, Ellison PT. Evolution in health and medicine Sackler colloquium: Evolutionary perspectives on health and medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jan 26;107 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):1691-5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914475107. PMID: 20133821; PMCID: PMC2868294.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20133821

103. Muskiet, F. A. (2018). Evolutionaire geneeskunde: De groei van onze hersenen heeft ons gevoelig gemaakt voor ‘typisch westerse’ziekten. Bijblijven, 34, 391-425.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12414-018-0318-2

104. Muskiet, F. A. J. (2005). Evolutionaire geneeskunde U bent wat u eet, maar u moet weer worden wat u at1. Ned Tijdschr Klin Chem Labgeneesk, 30(3), 163-184.

105. Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, Mann N, Lindeberg S, Watkins BA, O’Keefe JH, Brand-Miller J. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Feb;81(2):341-54. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.81.2.341. PMID: 15699220.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15699220

106. Natterson-Horowitz B, Aktipis A, Fox M, Gluckman PD, Low FM, Mace R, Read A, Turner PE, Blumstein DT. The future of evolutionary medicine: sparking innovation in biomedicine and public health. Front Sci. 2023;1:997136. doi: 10.3389/fsci.2023.997136. Epub 2023 Feb 28. PMID: 37869257; PMCID: PMC10590274.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37869257

107. Benton ML, Abraham A, LaBella AL, Abbot P, Rokas A, Capra JA. The influence of evolutionary history on human health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2021 May;22(5):269-283. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-00305-9. Epub 2021 Jan 6. PMID: 33408383; PMCID: PMC7787134.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33408383

108. Zhou MS, Wang A, Yu H. Link between insulin resistance and hypertension: What is the evidence from evolutionary biology? Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014 Jan 31;6(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-6-12. PMID: 24485020; PMCID: PMC3996172.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24485020

109. Gremer JR. Looking to the past to understand the future: linking evolutionary modes of response with functional and life history traits in variable environments. New Phytol. 2023 Feb;237(3):751-757. doi: 10.1111/nph.18605. Epub 2022 Dec 5. PMID: 36349401.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36349401

110. Watve MG, Yajnik CS. Evolutionary origins of insulin resistance: a behavioral switch hypothesis. BMC Evol Biol. 2007 Apr 17;7:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-61. PMID: 17437648; PMCID: PMC1868084.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17437648

111. Eaton SB, Cordain L, Lindeberg S. Evolutionary health promotion: a consideration of common counterarguments. Prev Med. 2002 Feb;34(2):119-23. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0966. PMID: 11817904.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11817904

112. Luca F, Perry GH, Di Rienzo A. Evolutionary adaptations to dietary changes. Annu Rev Nutr. 2010 Aug 21;30:291-314. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-080508-141048. PMID: 20420525; PMCID: PMC4163920.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20420525

113. Bateson P. Developmental plasticity and evolutionary biology. J Nutr. 2007 Apr;137(4):1060-2. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.1060. PMID: 17374677.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17374677

Nutrients in meat

114. Kavanaugh M, Rodgers D, Rodriguez N, Leroy F. Considering the nutritional benefits and health implications of red meat in the era of meatless initiatives. Front Nutr. 2025 Jan 27;12:1525011. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1525011. PMID: 39935586; PMCID: PMC11812593.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39935586

115. Omaye AT, Omaye ST. Caveats for the Good and Bad of Dietary Red Meat. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019 Nov 12;8(11):544. doi: 10.3390/antiox8110544. PMID: 31726758; PMCID: PMC6912709.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31726758

Bone quality in the past

116. Holt BM, Formicola V. Hunters of the Ice Age: The biology of Upper Paleolithic people. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2008;Suppl 47:70-99. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20950. PMID: 19003886.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19003886

117. Agarwal SC, Dumitriu M, Tomlinson GA, Grynpas MD. Medieval trabecular bone architecture: the influence of age, sex, and lifestyle. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2004 May;124(1):33-44. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10335. PMID: 15085546.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15085546

118. Agarwal SC, Grynpas MD. Bone quantity and quality in past populations. Anat Rec. 1996 Dec;246(4):423-32. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199612)246:4<423::AID-AR1>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID: 8955781.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8955781

119. Agarwal SC, Grynpas MD. Measuring and interpreting age-related loss of vertebral bone mineral density in a medieval population. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2009 Jun;139(2):244-52. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20977. PMID: 19140184.

MMV maakt wekelijks een selectie uit het nieuws over voeding en leefstijl in relatie tot kanker en andere medische condities.

Inschrijven nieuwsbrief